Zbigniew Herbert, “The Envoi of Mr. Cogito”

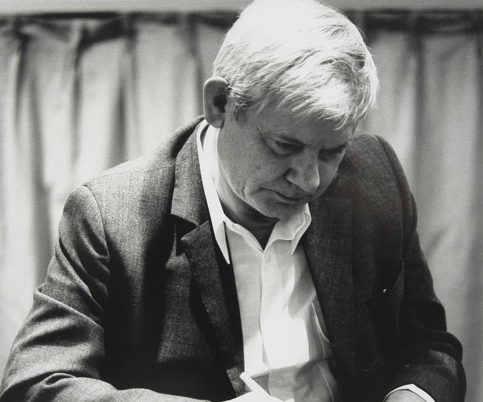

Zbigniew Herbert

I wrote most of this essay as part of my ‘teaching’ in an introductory poetry class. When I sent it by email to my poetry list, I explained how I had come to write about a second poem by Zbigniew Herbert. (The first poem I sent out, which is the second letter about a poem on these pages, was Herbert’s “Five Men.”)

Let me offer two brief explanations to illuminate what follows. The first is easy: I originally wrote to my students, and as you who are reading this know by now, I think poems shed light on other poems. We live in a wonderfully interlinked network of texts. In the largest sense, our language is the network of all texts. But for each of us, there is a network of texts we have read and, hopefully, recall.

Thus, in writing about Herbert’s poem, I at times tried to relate it to other poems my students had read, poems by Frost and Herbert himself. I have retained these references, even though you have not taken that class.

The second explanation has to do with my motives in assigning this poem to my students and in sending it out to my list. It is hard to know how to live. Our lives are spent, as we go along, learning how to live. We are not born with much along those lines, other than a tendency to suck and get nourishment, and a startle reflex which protects us from rolling over and perhaps rolling into trouble. As Theodore Roethke wrote in one of the great villanelles in English, “The Waking,” “I learn by going where I have to go.” Which, as I am sure you will see if you think about the line, has two possible meanings: we learn through the necessity of having to go through things, and we learn through the process of living where we have to go as we move forward.

Now in assigning this Herbert poem to my students and in addressing it in the manner I did, I treat Herbert as a great teacher of ethics. His poem tells us how to live. He says things to us that we do not hear very often, especially in a society where we rank among our highest values being a smart shopper and a popular Tweeter.

Can a teacher, should a teacher, of literature be a teacher of how to live an ethical life? That question is a serious one, but in an important sense it points to the separation of functions that has attended on modern men and women. Priests, rabbis, ministers, imams are figures who are supposed to show us the moral way; English teachers are supposed to teach students how to read texts and how to write clearly. (Physics teachers are supposed to teach about levers, about electrons, about dwarf stars.)

In class, I try to keep politics, which I rarely address, separate from the ‘content’ of my courses. But who will teach the young, and the not-so-young, how to live? That was the question which was at the heart of Socrates’ mission[1]. Isn’t that still one of the major concerns we should have? And isn’t Socrates’s great self-criticism, which was that he was aware how little he understood, how little claim he could have to ‘the truth,’ still a remarkably fine counsel to us as we, too, search for how to live our lives?

I assigned this poem to my student, because I believe Herbert has something important to teach us. More than any other poem in this volume, “The Envoi of Mr. Cogito” is intent on educating us about ethics, about what is good and what is good for us. Its lesson, as the poem makes clear, is not about any easy path, and the course it counsels is remarkably hard to follow.

The poem stands, for me, as one of the great ethical pillars of the twentieth century.

Here is what I sent out to the my list subscribers about this analysis, after which the analysis follows:

Prefatory Note:

I am teaching two classes this semester, an introduction to poetry and an advanced course called “Poetic Revolutions.”

In the “Poetic Revolutions” course several days ago we read poems by the powerful and important black American poet, Imamu Baraka. I have an ambivalent relation to those poems, which are powerful and angry but which in their rage push into terms and phrases which are deeply insulting to Jews, Italians, the Irish, women and gays. Anger and insult: it was a harrowing place to be. No one says poetry needs to be either comfortable or comforting, but if a poem lessens rather than deepens our humanity, we can certainly ask questions about it.

Shortly afterwards I sent the students an email to remind them of the assignment for the next class, a number of late poems by Pablo Neruda. I wrote “Neruda is, to my mind, the sunniest, most joyful poet we read all semester. (The poems we will read are by the Neruda who was older; as a poet, he changed a number of times in his life. Not all his poetry is sunny like this.) I think you will not only enjoy, but love, his poems. Well, I hope so.”

When I awoke on Thursday morning, I had one of those rare days when I did not want to leave the house, did not want to go to work. The day was cold and grey, I had slept badly, the semester had reached a point not just for me but for students too when it seemed endless.

But nonetheless I got dressed, had breakfast, and set out for work. As I walked to my office I thought, ‘If you are feeling down, and doubtless the students are too, why don’t you teach the students in the intro class the joyous poems you announced to your more advanced class?’ It seemed like a good idea to me and so I did exactly that. I don’t know if they felt joyous after a class on Neruda, but I certainly did.

By reading Neruda with those first-year students I skipped a great masterpiece of a poem, Zbigniew Herbert’s “The Envoi of Mr. Cogito.” Though I thought it made good sense to look at Neruda, I didn’t like the idea of skipping over the Herbert poem. So I informed the students, at the start of class that although we would be reading Pablo Neruda[2], I would send them an email about Herbert’s wonderful poem.

I wrote that email, and sent it out, and here it is.

The Envoi of Mr. Cogito

Go where those others went to the dark boundary

for the golden fleece of nothingness your last prizego upright among those who are on their knees

among those with their backs turned and those toppled in the dustyou were saved not in order to live

you have little time you must give testimonybe courageous when the mind deceives you be courageous

in the final account only this is importantand let your helpless Anger be like the sea

whenever you hear the voice of the insulted and beatenlet your sister Scorn not leave you

for the informers executioners cowards—they will win

they will go to your funeral and with relief will throw a lump of earth

the woodborer will write your smoothed-over biographyand do not forgive truly it is not in your power

to forgive in the name of those betrayed at dawnbeware however of unnecessary pride

keep looking at your clown’s face in the mirror

repeat: I was called—weren’t there better ones than Ibeware of dryness of heart love the morning spring

the bird with an unknown name the winter oaklight on a wall the splendour of the sky

they don’t need your warm breath

they are there to say: no one will console yoube vigilant—when the light on the mountains gives the sign—arise and go

as long as blood turns in the breast your dark starrepeat old incantations of humanity fables and legends

because this is how you will attain the good you will not attain

repeat great words repeat them stubbornly

like those crossing the desert who perished in the sandand they will reward you with what they have at hand

with the whip of laughter with murder on a garbage heapgo because only in this way will you be admitted to the company of cold skulls

to the company of your ancestors: Gilgamesh Hector Roland

the defenders of the kingdom without limit and the city of ashesBe faithful Go

[Translated from the Polish by Bogdana Carpenter and John Carpenter]

It is not good practice to begin an essay with a dictionary definition, but I will violate that general rule in order to tell you what an ‘envoi” is. Webster’s defines it thusly: “the usually explanatory or commendatory concluding remarks to a poem, essay, or book; especially a short final stanza of a ballad serving as a summary or dedication.” Clearly, what we have in “The Envoi of Mr. Cogito” is not a concluding stanza. Instead, we are meant to see this poem as the last in the long series of Mr. Cogito poems that Zbigniew Herbert wrote over more than three decades[3].

You in my class will recall from the first Mr. Cogito poem we looked at that Mr. Cogito gets his name from Descartes’s famous statement, Cogito, ergo sum: ‘I think therefore I am.’ He represents the rational; he is, I believe, an everyman, a kind of average person standing in for all of us. He is an ironic protagonist and sometime narrator, not as smart as Zbigniew Herbert himself, but always reasonably perceptive and always honest. He’s a stand-in, after a fashion, for the poet, simpler but no less wise. Behind his unwillingness to accept simple or sentimental answers lies a kind of courage, and that courage is a variant of what this poem counsels.

“The Envoi of Mr. Cogito” begins with an exhortation to take on the mantle of the hero:

Go where those others went to the dark boundary

for the golden fleece of nothingness your last prize

Notice it is a command, the verb in the imperative: Go! The command is to go beyond the easy and safe, the places of light. It insists that we readers follow after the hero of myth, Jason, who with his Argonauts set out to capture the Golden Fleece and thus prove that he could wear the mantle of kingship. Though for us in our belated and unheroic times there is no similar reward: heroism must be its own intrinsic reward, since for us today there is neither victory not kingship, only “nothingness.”

The second stanza demands we act heroically, standing upright while others are “on their knees” worshipping or acting subserviently to powers we courageous ones will not be acknowledging. Let us consider the context in which Herbert was writing, a context you will want to bear in mind as you read the poem and what it demands of us.

Herbert’s poetry was written in Poland, at that time under the subjection of the Soviet Union. Poland was an authoritarian police state – Herbert was harshly treated, in part for writing poems like this – a political condition which would not end until after the popular labor movement Solidarity challenged the communist authorities in 1980. So when Herbert speaks of people on their knees, he is referring to his immediate context, submission to communist rule. Yet he is also speaking to the larger condition of modern men and women[4], all of us, in his view, subject to mass culture, the degradation of values, the erosion of ethical principle.

Here, then, are the second and third stanzas of “The Envoi of Mr. Cogito”:

go upright among those who are on their knees

among those with their backs turned and those toppled in the dustyou were saved not in order to live

you have little time you must give testimony

The third stanza is, to my mind, the most important in the poem. The speaker claims life is about more than survival; in historical context, readers in Poland would be aware of the destructive Nazi occupation, the horrible exterminations of the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Treblinka, the Second World War, the Soviet takeover. But the larger context is also present: that life, as I just said, is about more than survival. We survive in order to give witness. To repeat his line, “you have little time you must give testimony.”

Herbert is defining what he believes is the central function of poetry in our time. His poetry is the poetry of witness. Much, much of his poetry says, ‘This is what has happened to me and to others in our time, which is a difficult time. Deaths go unnoticed, alienation is all around, ethics are forgotten in an embrace of relativism and government propaganda. Men have been and are horribly destructive. We must not gloss over, pass by or forget what has happened in our time.’

Although his poetry is stark, there is always in Herbert always an alternative to death, alienation, relativism, ethical disregard. Mr. Cogito, the persona of so many of his poems, is not always brilliant or even overly sensitive, but he struggles to see what is before him and to try to act in good faith as he encounters what he sees. This whole poem, this “Envoi,” exemplifies this dual role of witnessing and trying to find an ethical way forward.

Which is why the speaker commands us to “be courageous:”

be courageous when the mind deceives you be courageous

in the final account only this is importantand let your helpless Anger be like the sea

whenever you hear the voice of the insulted and beaten

Resist deception, act with courage: “In the final account only this is important.” One of the things I most admire in Herbert is his willingness to state, directly, without ornament, basic truths as he sees them. We tell stories to children exemplifying the worth of being ‘courageous.’ When people are mobilized into the armed forces in wartime we tell them the same thing. However, in the endless round of daily life we hardly ever hear those words, these exhortations to courage. And yet Herbert reminds us that nothing else is important: only honesty and courage, and, in the next stanza, a deep anger at the injustice and brutality of men who beat and insult and put down other men and women.

Scorn those, Mr. Cogito says, who are not ethical or brave, even though in today’s world they will end up the winners. It is not, he insists, about winning, no matter how much the football coaches or Donald Trumps of the world may tell you it is. There is something very brave in these lines, which command us to live an ethical life even if there are no rewards, even if we will not be remembered for our courage.

let your sister Scorn not leave you

for the informers executioners cowards—they will win

they will go to your funeral and with relief will throw a lump of earth

the woodborer will write your smoothed-over biography

Act heroically and even in retrospect there will be no reward. You will be buried and history will be sanitized so that your heroic resistance will be forgotten.

The speaker even challenges Christianity, eschewing turning the other cheek for somewhere ‘beyond good and evil,’ to use Nietzsche’s term. He wants us to move beyond what we too often and maybe too easily think is the source of ethical action. This is a poem about courage, not love:

and do not forgive truly it is not in your power

to forgive in the name of those betrayed at dawn

Ouch. Withhold forgiveness. Too often it is only the worst among us, the rabid politicos on the right fringe of our politics, who evince no forgiveness. Yet even on the right, people are loathe to say “do not forgive,” and if they do they are not in accord with these lines, which insist on an ethical perspective: forgiveness for those who harm others is not ours to bestow, since the wrongs committed were not against us.

What follows are warnings, a series of commands to “beware!” Beware of pride, since you, like all men and women, are more clown than hero even as you strive to be courageous. Beware of pride since the best may lack the conviction[5] and so history has only you, with your frailties, to call on. Don’t retreat from life and its dangers into “dryness” and revulsion against the world. “Love.[6]”

beware however of unnecessary pride

keep looking at your clown’s face in the mirror

repeat: I was called—weren’t there better ones than Ibeware of dryness of heart love the morning spring

the bird with an unknown name the winter oaklight on a wall the splendour of the sky

they don’t need your warm breath

they are there to say: no one will console you

Love he says, ‘all the loveliness of the world[7]’. We can and must love, Herbert claims, while realizing that the spring, the bird, the oak, the light, the sky do not need us[8].

I feel I have to intrude, here, to say that not all poets feel this way. In his great poetic sequence, the Duino Elegies, Rainer Maria Rilke claims exactly the opposite, that the things of this world need us, need us most of all, to bear witness to them and their loveliness.

How can Herbert say one thing and Rilke the opposite? We always need to remember that poems do not deliver ‘the truth’ but things that the poet perceives, believes, might be the truth as she or he writes the poem. How we see things: we can differ, not only with others, but within ourselves[9].

Back to Mr. Cogito and Zbigniew Herbert. Since the glorious things of this world do not need us, they do not, cannot, offer us consolation. For us, there is the going forward even without the consolation we seek. Mr. Cogito advises us to “be vigilant” for the sign that it is time to move into battle, even if the battle is joined only by the act of giving testimony:

be vigilant—when the light on the mountains gives the sign—arise and go

as long as blood turns in the breast your dark starrepeat old incantations of humanity fables and legends

because this is how you will attain the good you will not attain

repeat great words repeat them stubbornly

like those crossing the desert who perished in the sand

You, like the mythic heroes of old, must follow “your dark star,” the promptings of your blood, calling you to muster the courage to go forward.

On this journey forward, the poem tells us, you will have words, not the words of newspapers or speeches or even books, but “old incantations of humanity fables and legends.” Courage is required as we move forward, as we face the trials of our own day. And what do we have to sustain us? The story of Jason, or of other heroes; sacred words like love and beauty and truth and courage. We must “repeat great words repeat them stubbornly” even though we will not win. Winning in our day, facing in whatever form (fascism, communism, monopoly capitalism, the polite policed society) what the novelist Norman Mailer once termed “the murderous liquidations of the state,” does not allow for victory but only issues in a perishing in the harsh desert of our days.

This is a hard view of contemporary life and you are not bound to agree with Mr. Cogito and Herbert. But if we are courageous, as the poem commands us to be, we must consider whether perhaps he is right, whether he is telling us a truth we must acknowledge. That as Yeats noted in a late poem, “good men starve and bad advance.” We must ask whether our society and our world and sometimes we ourselves reward the crass and the craven and the cowardly while we ignore those who struggle for justice or freedom. Whether we adequately value those who in their daily rounds try to lead a ethical life.

I would suggest that being a ‘good person’ is not as easy as advertisements and television sometimes make it out to be, as if we can live a good life if we only buy a Mercedes or a Ford or a Rolex, or join the local Chamber of Commerce, or give money to the Red Cross or a contribute spare cans of food to provide the needy with a meal at Thanksgiving.

Courage. Mr. Cogito claims that those who shape our modern world will laugh at those with courage and tenacity and ethical standards, and those whom it cannot shape through corrosive humor it will kill and dishonor even in death:

and they will reward you with what they have at hand

with the whip of laughter with murder on a garbage heap

Tough lines.

This poem begins with the command to go forward with courage because there is no reward for the good life other than living it. Those who live well – and well here does not mean living in grand houses or with fast cars or expensive perfumes, but living ethically, living a moral life – can expect no reward but death.

The good life has sometimes brought heroism, but it always leads to death. Still, there is heroism in living an ethical life, for one can join the great heroes of the past: Gilgamesh (of ancient Mesopotamia, hero of the great Gilgamesh, who protected his people and learned of the reality of death), Hector (of ancient Troy, hero of the great epic The Iliad, who protected his people even though he died at the hands of Achilles) and Roland (of medieval France, hero of the great epic Le Chanson de Roland, who protected his people even though he too died in doing so).

All of the three heroes Mr. Cogito cites defend their own civilization, defend humanity with courage and dignity, and thus he calls them “the defenders of the kingdom without limit and the city of ashes”. Why the city of ashes? Because over time that is what we all become, hero and “informers executioners cowards” alike. But only the heroes, among whom we can strive to be included, are also “defenders of the kingdom without limits,” the defenders of what is good and just and right.

It takes courage, he begins by telling us, and requires us “to give testimony.” It requires that we be angry at those who use insults and beatings to put down other human beings. It requires us to withhold forgiveness that is not ours to grant, to avoid undue pride, to avoid a rejection of the world and embrace love, to be vigilant and pay attention, to study and take to heart old stories and the words that have always been with us. In this way, we will not attain any sort of tangible victory, “because this is how you will attain the good you will not attain.” But there is something we can do: we can live a good, an ethical life.

The poem ends, “Be faithful Go.” It commands us to go out into the world, and into the remainder of life, with courage and love and sensitivity to the old stories and the old words.

Let me conclude with a three memorable and connected passages by the American novelist William Faulkner, taken from his difficult but wonderful novella called “The Bear.” During the story, the protagonist Ike recalls how on a hunt while in the middle of the Mississippi wilderness his father talked to him about poetry, specifically about John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” That poem famously ends, “‘Beauty is truth, and truth beauty,—that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.’” Ike’s father says,

“He was talking about truth. Truth doesn’t change. Truth is one thing. It covers all things which touch the heart—honor and pride and pity and justice and courage and love. Do you see now?”

Then, at the end of their conversation, the father sums his view up, in words I think are very close to the “Envoi” we have just read:

“Courage, and honor, and pride,” his father said, “and pity, and love of justice and of liberty. They all touch the heart, and what the heart holds to becomes truth, as far as we know the truth. Do you see now?”

Finally, late in the novella, as if continuing this conversation, the young man says to his cousin McCaslin:

“And I know what you will say now: That if truth is one thing to me and another thing to you, how will we choose which is truth? You don't need to choose. The heart already knows.”

Faulkner’s young man, Ike, is articulating what Herbert tells us about “old incantations of humanity.” The old stories and the old words are true, and we should strive to live by them. It takes courage and humility: Living in this way does not hold any promise of success. But living by these old standards is the way, the only way in our difficult postmodernity, to “defend the kingdom without limit.” Courage in the effort to live an ethical life, to give witness, to defend the right, is in Herbert’s telling, the path of heroism in our contemporary age.

Footnotes

[1] The best book I have read in the past twenty years is a study of the origins of Western philosophy by Pierre Hadot, a French philosopher and intellectual historian. Also a teacher of the acclaimed social philosopher Michel Foucault. The study was published with the unpretentious title, What is Ancient Philosophy? and its controlling thesis is that the ancient philosophers – not just Socrates and Plato and Aristotle, but those who followed – all addressed one central question: How should we live?

[2] The Neruda poems I taught, on lemons, on tomatoes, on a pair of socks, on a suit, are all accessible on the web. No reason in grey November (and it is once again November as I revise this introduction) you too shouldn’t read joyous poems, poems which celebrate the things that surround us and which bring us so much delight, pleasure, joy. Just type in “Neruda lemons Peden” into Google. Substitute socks or suit for lemons for the other poems. The tomatoes poem can be found in on these pages as it is the subject of one of my analyses.

As for the “Peden,” I favor Margaret Sayers Peden’s translations. Although if you want to be daring, type in “Neruda socks Williams” and you will find a translation by one of the greatest poets of the century, William Carlos Williams, of Neruda’s great poem.

[3] Surprisingly, this was the first of the Mr. Cogito poems to be published. The summary is actually prologue, defining the stance Mr. Cogito would be taking toward the world.

[4] Let me remind you of Herbert’s “A Knocker, which I referred to when I wrote about Herbert’s poem “Five Men.” In “A Knocker” the poet defines a limited but essential goal in these hard modern times, which is to see what is true and what is not. That poem ends,

I thump – the board

and it prompts me

with the moralist’s dry poem

yes – yes

no – no

[5] Yeats wrote, famously, in “The Second Coming:”

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

[6] At this juncture in the mailing to my students I asked “Do you remember Robert Frost’s poem, “Birches,” where he so wonderfully insists that even with all its sufferings and troubles “Earth’s the right place for love?”

[7] That phrase comes from the strong but problematic poem “Black Art” by Imamu Baraka, the major African-American poet . If you recall the introduction to this essay, it was teaching Baraka, and this poem in particular, that led me to substitute Neruda for this Herbert poem in my introductory class…..

[8] I wrote to my students, ‘Frost, if you will recall, said something rather similar in “The Need to Be Versed in Country Things.’

[9]Also in my email to my students I wrote, ‘ I think I told you in class, early on, that Robert Frost once said the following words, but on making sure I had the quote right I realized I was wrong in attributing the words to Frost, since it was the Irish poet William Butler Yeats who wrote: “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.” We can, and do, disagree with ourselves.’

Truth is sometimes, even within in our own brains, a very complex matter. Though I will end with a statement by a character created by the novelist William Faulkner which will disagree profoundly with the last sentence I just wrote.