Theodore Roethke, “My Papa’s Waltz,” “I Knew a Woman,” “They Sing, They Sing”

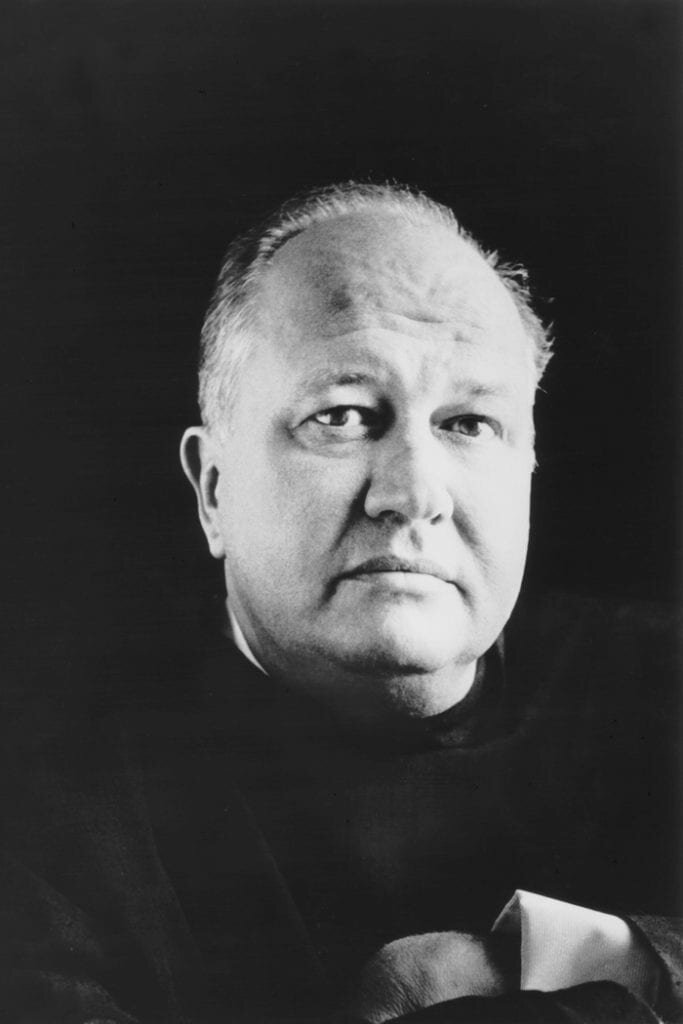

Theodore Roethke

My Papa’s Waltz

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother’s countenance

Could not unfrown itself.The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

Theodore Roethke is a vastly under-rated poet. Perhaps that is wrong: It is not so much that he has been under-rated, as that he has been forgotten.

As I thought about this letter, I went over, in my head, the history of my involvement with Roethke. Forgive me if I am being a bit self-indulgent here, but tracing the pattern of my love of certain poets may point toward something of substance.

In high school, I fell in love with e e cummings, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Robert Frost. The first two are less read today than they were then; with Frost, I have had a life-long attraction and simultaneous questioning, mostly along the lines of ‘Why was he modern? What, formally and stylistically, anchors him in his particular era?’

In college, I fell in love with Yeats and Wordsworth. Yeats has remained a enduring affection, although as my last letter revealed, I have had ‘a lover’s quarrel’ with him. (The phrase comes from Frost, who said he had ‘a lover’s quarrel with the world.’) My relation with Wordsworth was thornier: I really, really disliked him. Then one day as I was reading his long poem The Prelude he recounted an epiphany he had while climbing Mount Snowdon at night: And I had an epiphany as well. All of a sudden, in a flash which mimicked the flash of bright moonlight the poet encounters as he hikes upward through mist and fog, I saw what he was about. And I have loved Wordsworth ever since. I think he is the poet I most treasure.

In graduate school I discovered William Carlos Williams and Emily Dickinson. Neither disappoint, and they have been my lifelong companions ever since. As has Walt Whitman, whose words (quoting him) ‘itch at my ears.’

When I began teaching, I was overwhelmed by Sylvia Plath and Theodore Roethke. Plath I kept teaching until her underlying message – suicide – seemed to me an untenable thing to present to impressionable college students. Roethke? He slid slowly from my attention, and then for decades I did not teach him at all.

Why have I recounted this history? It is about Roethke. Somehow he receded from academic attention, and I was not steadfast enough to resist the tides of critical judgment. I think that says more about me than about Roethke. He was a great poet; he is a great poet. His eclipse is, in my view, tragic.

So why am I resurrecting Roethke? I taught a short course in American poetry, on-line, over Zoom, to ‘senior’ students. One of them, in a discussion about William Carlos Williams, mentioned that his college English teacher, five decades earlier, had thought highly of Roethke. ‘I’ve been reading him again,’ I answered, which was true but also obscured the fact that my slightly diminished view of him still prevailed.

So I went back and read more Roethke poems again. What a magnificent poet he was.

I think I know why he declined in both my view and critical favor. Neither reason is, to my current mind, satisfactory. I myself turned away from Roethke when I read that he kept a notebook. In it he often wrote lines that seemed wonderful to him; later, he would use these lines in poems he was writing or developing. I subscribe to the notion that poems come from a place deep within us, a place that wells upward and outward, like a hidden spring that becomes a pool or a brook. Poems are made, I know, constructed: I have no problem with revision and re-revision, with the poem as a made thing. But a thing constructed with bricks which pre-exist the poem’s coming into being? I had trouble with that. I believe in spontaneity, either sudden or in recollection, Wordsworth’s famous “emotion recollected in tranquility.” Roethke’s earlier lyrics seem spontaneous, but were the later poems ‘constructed’ of pre-existing building blocks?

And that brings me to why the critics seem to have abandoned Roethke. He did not write in one poetic ‘voice.’ He was always experimenting, and while connoisseurs could accept a change of style and method and even purpose in a painter (I think of the relentless movement of Picasso, from the blue and rose periods to cubism, to neo-classicism, to synthetic cubism: Always tirelessly and doggedly trying out and on; experimenting, reshaping, reforming, who he was and how he painted), I am not sure that connoisseurs and critics could accept such changes in poets. We want poets to burrow deeper into themselves, to add depth and maturity to what they write. They can change, as Yeats did several times, but we want the change to be a burrowing deeper.

Roethke wrote lyrics about his early life, about his tortuous relationship to his father in the greenhouses that his father, a grower of flowers, owned and dominated. (We will look closely at one of those poems, “My Papa’s Waltz”). Then he wrote more ‘conventional’ poems, poems of love and loss. We will look at another, “I Knew a Woman.” Then he wrote long poems of psychological introspection, poems which sought to inhabit a landscape best known to Jung and Freud. Then he wrote longer meditative poems, overly (in my view) influenced by the two poets he admired the most, T. S. Eliot and William Butler Yeats. They are perhaps too derivative….

Whatever the reasons for his changes, critics did not reward his relentless experimentation as much as they held it against him, as if he did not know who he was. Perhaps that is true: Who among us is secure in his or her identity, sure of how we sound, confirmed in our own ‘voice’? A useful fiction, that we have an inner identity that is the core of us, and which should breathe life into our poems. Roethke challenged that fiction, and for that challenge critics, I feel, could not forgive him. Unlike the Portuguese poet, Fernando Pessoa, he moved around: Pessoa from the start adopted ’heteronyms,’ various identities who were the ‘authors’ of poems which exhibited his various ‘selves.’

I’ve written a lot about both myself and about Roethke’s oeuvre, maybe more than I should have. But he represents a major quandary for the reader of poetry. We all know poets can be ‘discovered’ years after they have written their poems, as was the case with Hopkins and Whitman and especially Dickinson. We all know poets can be esteemed in their time, and found by later readers to be shallower than was known at the time.

But that a great poet can just fade into a pale semi-oblivion? Roethke is that sort of poet. One of the great American poets, an original in many ways, and yet aside from older folks who remember reading him in college, rather forgotten.

“My Papa’s Waltz” is a poem of four stanzas, each rhyming ABAB. (breath/death, easy/dizzy. You get the idea.) The metrical pattern is not as regular, since it is inflected by what are called feminine rhymes, where the final syllable is unstressed. Although largely in iambic form (an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable), in alternating stanzas there is an additional unstressed syllable at the ends of alternating lines – the feminine rhyme – (lines 2 and 4, with ‘dizzy’ and ‘easy;’ lines 10 and 12, with ‘knuckle’ and ‘buckles.’ These lines have seven syllables, and does the 15th line.) Regularity, but enough of an interruption to the pattern to make it interesting and not fully predictable. So we can say that this is a poem in iambic meter, with the first and third stanzas making use of alternating masculine and feminine rhymes.

More than you wanted to know, perhaps. Still, we need to be attentive to the pattern of sounds: The musical dimension of a poem is not only integral to the poem, it is what enables the poem to say ‘more’ than prose can say.

Let’s look at the four stanzas, each in turn.

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We are observing a drunken dance, in which the son is dazed (“dizzy”) by the circumstance, dancing with his father, and his drunk father at that. Drunk or at least partially so: “The whiskey on your breath.” We sense that the boy is frightened, for he holds tightly – “I hung on like death” – in a dance that is not only awkward but difficult to endure. (“Such waltzing was not easy.”) “Like death?” Robert Frost wrote a wonderful line, insisting that at times “the work is play for mortal stakes.” That is the case here. The dance with his father is perilous, not just because of danger of injury, but because the central relationship in the young boy’s life, his relation to his father, is at stake. Of course, with such complexity hanging over this dance, the “waltzing was not easy.” The boy is terrified, just trying to hang on to his drunk father. It is not, as the final line of the stanza tells us, an easy endeavor.

The second stanza describes the dance and its lone observer at the time, the boy’s mother; Roethke the poet of course is an additional watcher, observing in the future, when he writes this poem, this moment from his past.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother’s countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

We have just learned the dancing is not easy, and yet here – desperate play – the father and son are ‘romping.’ Those pans on the shelf are images of disorder, disruption. Of violence, for the waltz is not sedate, is not civilized ritual movement, but is rather the lumbering of a drunken father who grabs his child tightly as they carouse through the kitchen. Much is conveyed by the double negative (not/un-) of the stanza’s final line. The mother frowns in disapproval as her husband grasps her son and moves through the room in a sort of dance. But it is more than disapproval: She is powerless to intervene, to stop the drunken “romp.” There will be no rescue here, for although she disapproves, all she can do is show her disapproval in a manner that cannot (those negatives!) alter the situation.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

We will want to pay attention to pronouns here. Although there is a ‘you’ in the third line of the stanza, the hand is not ‘your’ hand but ‘the’ hand, indicating that the dance has its own insistence, its own imperative. That hand is somehow not controlled, even if it is controlling.

We are encountering close observation here: Not only is the boy held as a partner might be in a waltz, the hand which holds him “was battered on one knuckle.” Again we encounter an image of violence (“battered”) but here the hurt has been suffered by the child’s father. We are encountering a sign of class: His father is a working man, a man who labors with his hands, hands which show the signs of physical labor. (Even though his father owned the greenhouses in which he worked.)

Caught in that perilous grip, the boy is himself battered. As his drunken father “romps” with him, the father who tightly “held my wrist,” the son is subjected to unintended – but nonetheless real – violence, “scraped” by the buckle of his father’s belt. From the battered knuckle to the scraped ear: the poem hints that violence descends in families, that what has scarred the parent in some manner becomes what the parent inflicts upon his child. The “battered knuckle” of the father begets the ‘scraping’ of the son.

Roethke is not forgiving of the violence wreaked by the father in this poem, of the terror he inflicts. But he does note, I think, that the harsh conditions in which the father works beget the harshness that he perpetrates upon his son.

Those harsh conditions, and the dirty hands of the manual laborer, are reinforced in the final stanza. “With a palm caked hard by dirt” the father “beat time,” pounding the music’s rhythm on the head of his son. The father, here, is the worker, the provider, the elemental father; he is also violent, desperately loving but at the same time uncaring. The image is of a father merciless and violent.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

That astonishing ending! The dance is almost over – it concludes with the child in bed – and the dance is nearing conclusion. Has there ever been such a waltz in literature: Desperate, violent, abusive? Yet. Yet the child ‘clings’ to his father, dependent although abused, hanging on even though he is in peril. The child loves his father. I know, I know, the word ‘love’ as usually applied does not apply here. There is no reciprocity, nothing but “clinging’ on for dear life. But love comes in difficult forms, often ambivalent forms. The child in this poem fears his father, is terrified by him. But this father is the only father he has, and despite the violence of their relationship, he ‘clings’ to him. It is after all “My Papa’s Waltz,” as the title announces. After the dance, bed and perhaps sleep. But the key word here, and in the whole poem, is “clinging.” This is the relationship he has.

The poem recapitulates the long relationship between father and son. Terror, a strange sort of music, dependence. One thinks of the famous opening line of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” And this was Roethke’s family, reduced to sixteen lines, lines simple and yet full of complexity.

Here, from shortly later in his life, is one of the most wonderful love poems ever written. This is about a very different sort of love than the ‘love’ recounted in “My Papa’s Waltz.”

I Knew a Woman

I knew a woman, lovely in her bones,

When small birds sighed, she would sigh back at them;

Ah, when she moved, she moved more ways than one:

The shapes a bright container can contain!

Of her choice virtues only gods should speak,

Or English poets who grew up on Greek

(I’d have them sing in chorus, cheek to cheek).How well her wishes went! She stroked my chin,

She taught me Turn, and Counter-turn, and Stand;

She taught me Touch, that undulant white skin;

I nibbled meekly from her proffered hand;

She was the sickle; I, poor I, the rake,

Coming behind her for her pretty sake

(But what prodigious mowing we did make).Love likes a gander, and adores a goose:

Her full lips pursed, the errant note to seize;

She played it quick, she played it light and loose;

My eyes, they dazzled at her flowing knees;

Her several parts could keep a pure repose,

Or one hip quiver with a mobile nose

(She moved in circles, and those circles moved).Let seed be grass, and grass turn into hay:

I’m martyr to a motion not my own;

What’s freedom for? To know eternity.

I swear she cast a shadow white as stone.

But who would count eternity in days?

These old bones live to learn her wanton ways:

(I measure time by how a body sways).

Once again, four stanzas, although there are more poetic tropes here than we have just encountered. And each line ends with a parenthesis! The rhyme scheme is awkward in the first stanza, and quite regular thereafter. Stanzas two and four are greatly regular: ABABCCC: alternating rhymes concluding with a triple rhyme. In stanza three the final rhyme of that triple is a slant rhyme (ABABCCC’ – goose/seize/loose/knees/repose/nose/moved).

Ah, the first stanza. Those first four lines are loosely slant rhymes (bones/them/one/contain). I suppose we can project back from the ABAB rhymes of the other stanzas (bones/one being the A, and them/contain being the B, but ‘contain’ puzzles me, being a slant rhyme to both ‘them’ and ‘one). Strange, that the regularity increases as the poem proceeds!)

I could, and maybe should, work through all the imagery with you. But let me be clear: I love this poem, and the perfection of how it works, and part of why I love it is that it is the opposite of “My Papa’s Waltz.” Sophisticated where the earlier poem was simple and earthy, filled with the sort of imagery that we associate with poetry, witty and not desperate, full of praise rather than a despairing look at the complexity of origins.

So let me point out how wonderful this poem is: A praise of women in general, and one woman in particular. A paean to the glories of sex.

I knew a woman, lovely in her bones,

When small birds sighed, she would sigh back at them;

Ah, when she moved, she moved more ways than one:

The shapes a bright container can contain!

Of her choice virtues only gods should speak,

Or English poets who grew up on Greek

(I’d have them sing in chorus, cheek to cheek).

Ah, lovely to the very depth and structure of her, “lovely in her bones.” She could make small sounds, like birds, and was responsive to the natural world in which she moved -- “Ah…she moved more ways than one,” her body later moving “in circles, and those circles moved.” Such grace and variety. I do not think I need explain. Nor will I address that perfect line, “The shapes a bright container can contain !” Followed by what seems to me witty humor: “Of her choice virtues only gods should speak” – godlike is this woman, and only the language of gods is capable of speaking of her virtues – or perhaps those poets fluent in the language of those who invented those ancient deities: “Or English poets who grew up on Greek.” And that lovely concluding parenthesis, in which he envisions, to praise the love of his life, English poets singing “in chorus” and with a closeness and intimacy, “cheek to cheek.”

Praise. Pure praise.

In stanza two and also stanza three, she is the teacher and he is her student. There is an obvious sexuality to the lines, a sexuality hinted at by the first stanza’s “when she moved, she moved more ways than one.”

How well her wishes went! She stroked my chin,

She taught me Turn, and Counter-turn, and Stand;

She taught me Touch, that undulant white skin;

I nibbled meekly from her proffered hand;

She was the sickle; I, poor I, the rake,

Coming behind her for her pretty sake

(But what prodigious mowing we did make).

The “Turn, and Counter-turn” are phrases which describe the choruses of Greek plays – strophe and antistrophe. The line suggests that he learns something about poetry from her, but they also suggest various positions of love-making. After all, “She taught me Touch, that undulant white skin.” The body of his love(r), presented in the poem’s opening lines, is here sexualized, as he learns from her what she wishes and how he might respond to those wishes: “She stroked my chin…I nibbled meekly from her proffered hand.” Here he is the “birds” of the second line of the poem. They harvest: There is a sexual congress between them, in which he follows her and her lead, “coming behind her.” “(But what prodigious mowing we did make.)” I suppose we might read “rake” as a male enticed and enticing by sex; more obviously, he harvests and gathers together where she has shown him the way.

Love likes a gander, and adores a goose:

Her full lips pursed, the errant note to seize;

She played it quick, she played it light and loose;

My eyes, they dazzled at her flowing knees;

Her several parts could keep a pure repose,

Or one hip quiver with a mobile nose

(She moved in circles, and those circles moved).

More birds, now the goose, who is clearly the focus, the female to the male of the species. Her lips entice (“her full lips pursed”) as she takes every opportunity to teach him the delights of bodies. And her body! What “knees’ and legs, which dazzle him! She could be at rest, and yet quivering with a desire which leads him on. “(She moved in circles and those circles moved.)” We are back at stanza one, “when she moved, she moved more ways than one.”

The female body has him in thrall, and he has much to learn.

Let seed be grass, and grass turn into hay:

I’m martyr to a motion not my own;

What’s freedom for? To know eternity.

I swear she cast a shadow white as stone.

But who would count eternity in days?

These old bones live to learn her wanton ways:

(I measure time by how a body sways).

In thrall. “I’m martyr to a motion not my own.” Roethke turns philosophical, only to reject philosophy for the pleasures promised by his lover’s body. “What’s freedom for? To know eternity.” So he rejects thinking for pure pleasure, for the immediacy of the body: “I swear she cast a shadow white as stone.” He is, as he said of his eyes in the previous stanza, “dazzled.”

They have mowed, for now the cycle of grass is complete: “Let seed be grass, and grass turn into hay.” Remember, just two stanzas earlier, when “She was the sickle; and I, poor I, the rake”? But cycles are irrelevant, for “who would count eternity in days?” He is indeed the student, and what he learns is that sex and the body control our lives, and happily so: “These old bones live to learn her wanton ways.” I can think of no greater rejection of the philosophical, introspective, ideational life than the concluding parenthesis: “(I measure time by how a body sways.)” Or, as Walt Whitman wrote in equally wonderful lines, perhaps my favorite lines in all of poetry:

I too had been struck from the float forever held in solution,

I too had receiv’d identity by my body,

That I was I knew was of my body, and what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

Now for one final poem by Roethke, or rather a part of one. Later in his life he wrote a long, five-part poem called “The Dying Man: in memoriam W. B. Yeats.” I will refer to the whole poem (the link I just provided has a few textual mistakes! Corrected in the endnote.), but I want particularly to show you the final section, “The Sing, They Sing.” I have bolded the lines I particularly like.

5. They Sing, They Sing

All women loved dance in a dying light–

The moon’s my mother: how I love the moon!

Out of her place she comes, a dolphin one,

Then settles back to shade and the long night.

A beast cries out as if its flesh were torn,

And that cry takes me back where I was born.

Who thought love but a motion in the mind?

Am I but nothing, leaning towards a thing?

I scare myself with sighing, or I’ll sing;

Descend O gentlest light, descend, descend.

O sweet field far ahead, I hear your birds,

They sing, they sing, but still in minor thirds.

I’ve the lark’s word for it, who sings alone:

What’s seen recedes; Forever’s what we know!–

Eternity defined, and strewn with straw,

The fury of the slug beneath the stone.

The vision moves, and yet remains the same.

In heaven’s praise, I dread the thing I am.

The edges of the summit still appall

When we brood on the dead or the beloved;

Nor can imagination do it all

In this last place of light: he dares to live

Who stops being a bird, yet beats his wings

Against the immense immeasurable emptiness of things.

The whole of the poem, all five parts of it, are it seems to me about Yeats, the lyrical Irish poet, and how Yeats has come to replace Roethke’s father as the paternal guiding figure for his life. In the first section – the first two sections have a Yeatsian rhyme scheme and rhythm – he concludes that he has, finally, learned what it is to be a poet: “I am that final thing,/A man learning how to sing.” In the next stanza he expressly rejects what he learned from love, as he recounted it in “I Knew a Woman”:

I burned the flesh away,

In love, in lively May.

I turn my look upon

Another shape than hers

An older Roethke is now facing death, coming to the end of his days, and in this situation he looks to Yeats as a teacher. Even though he earlier focused on his father – we think of “My Papa’s Waltz” which attempted to cope with their complex relationship; later he wrote about his search for his father in a famous long poem, “The Lost Son” – Roethke recognizes as he faces death that his relation to his biological father is too narrow, too constraining. There is more than the son/father relationship to guide us as we try to fathom life. “I found my father when I did my work,/Only to lose myself in this small dark.” The subject of their paternal/filial relationship, now that he is older and has perspective, is small. The smallness, I should warn, is not commensurate with the vast “immense immeasurable” with which the poem concludes, an immense emptiness with which we have to cope.

This paragraph you are about to read is exactly the sort of thing you probably think English teachers orate about, which is why you might skip this entire paragraph. Anyway, here goes: As with “I Knew a Woman,” bird imagery abounds. Roethke aspires to be a bird confronting the infinite; he is small but specific. (Is it wrong to see the bird at the end of Yeats’s most famous poem, “Sailing to Byzantium” here? A bird who sings to enable us to endure existence,

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

The section abounds with references to Yeats’s poems and philosophy, from the “bee-loud glade” of “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” to the “beast” of “The Second Coming” (and the first stanza of this ultimate section of the poem) to his purported philosophy as expressed in the (to me interminable and wacky) A Vision: He even writes, “The vision moves,” referring perhaps both to that book and to the conclusion to “The Second Coming.”

See what I meant earlier, when I wrote that Roethke took on too many voices, and perhaps in doing so his ‘own’ voice got lost? Here the texture is so allusive that we, or at least I, can lose Roethke himself.

Still, I put this poem before you because of this concluding section, “They Sing, They Sing.” Its words, those I highlighted above, haunt my imagination.

To be truthful, I am not sure what these lines mean. I have a suspicion in focusing so tightly on these lines I am doing exactly what I chastised about, what I disliked in, Roethke’s poetic practice. He wrote down lines that sounded so good, so good, in his notebook. And now I am ignoring the ‘whole’ poem to highlight a handful of lines!

All I can say is that two segments, of three lines and four lines, live in my imagination, structure it in ways I do not understand, time and again. I do not think I understand the lines, do not understand them at all. But nonetheless they resonate in my inner ear, and have for decades. Sometimes all one can do is praise.

First, these descending lines, for the rhythm seems to gently abate and diminish, about descending:

Descend O gentlest light, descend, descend.

O sweet field far ahead, I hear your birds,

They sing, they sing, but still in minor thirds.

Let me suggest you read these lines aloud. I would be surprised if you do not find that they do descend: They are lovely, are they not?

I have no idea what the minor thirds refer to, but that gentlest light, whatever it is: I would wish it to descend upon me. Dylan Thomas, whom I have also been rereading, said ever so powerfully,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Roethke is, perhaps, saying the opposite. But whatever the lines ‘mean,’ they are so lovely. So lovely.

And the poem’s conclusion:

Nor can imagination do it all

In this last place of light: he dares to live

Who stops being a bird, yet beats his wings

Against the immense immeasurable emptiness of things.

What do these lines ‘mean’? That, like Sisyphus, we must continue pushing our rock up the hill, keep singing in the face of ‘emptiness’? Imagination clearly does not suffice as we encounter that “emptiness of things” that we know is out there, beyond us, around us. Yet we must keep singing – well, maybe not, because we “stop[] being a bird.” But we must still, like a bird, fly into the dark empyrean, the endless blackness that we do not accept: Note that “against:” “Yet beats his wings/ Against.” What surrounds us, the beautiful sounding but overwhelming “immense immeasurable emptiness of things” is what we must beat our wings against. [Would we be wrong in hearing an echo of that other, earlier, ‘beating against’ that ends F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby? “So we beat on, boats against the current…”?] Maybe this is what we have, beating our wings “against the immense immeasurable emptiness of things.”

Despite making some grasping and inclusive comments on these lines, I do not understand them. But I do hear them, and have heard them almost weekly, and have lived with them for fifty years. The lines ring in my ears.

In the end, what we have is fragments of poetry, lines which echo in our minds and echo again and echo once more.

Explication fails us. We have words and their music, descending, descending, beating our wings against the immense immeasurable emptiness of things.

You can find all the poetry letters at: https://www.huckgutman.com/

Sign up to receive future poetry letters by putting your name on the mailing list at: https://www.huckgutman.com/contact

Corrections to the web version of “The Dying Man”

Section 2 line 3, ‘hand’ should be ‘hands’

Section 3 second stanza, line 2 ‘and image pure’ should be ‘an image pure’

Section 3 second stanza, line 5, ‘figures our of’ should be ‘figures out of’

Section 3, the final line should end with a question mark: ‘behind the sun?

Section 4, first stanza, ‘after image’ should be ‘after-image’

Section 4, fourth stanza, last (sixth) line, ‘dying with my death.’ should be ‘dying by my death.’

Section 5, second stanza, line 5 ‘I sweet field far ahead’ should be ‘O sweet field far ahead’

Section 5, third stanza, line 2, ‘What’s seen recededs’ should be ‘What’s seen recedes’