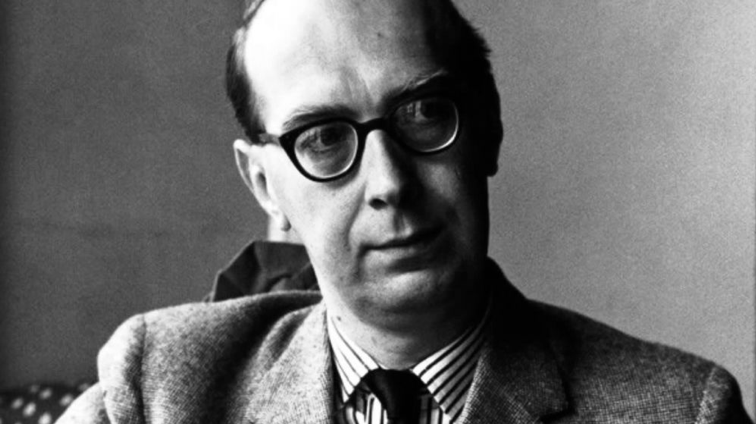

Philip Larkin, Three Poems: “This Be the Verse,” “Mower,” and “Aubade”

Philip Larkin

This Be The Verse

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

I have always been attracted to poets who write directly, poets who use the language that people speak in daily life. I love Wordsworth and Whitman and Williams, in part because of their language. Their language goes with a directness that is the opposite of ‘fine’ poetry. It is easier for people to claim they love Keats rather than Wordsworth, Tennyson rather than Whitman, Eliot rather than Williams, because we so often associate a heavy dose of figurative language, an ornate vocabulary, ‘difficult’ meanings, to the simple language and seemingly simple ideas that are to be found in Wordsworth and Williams.

Many of the poets I love best in the twentieth century – save Rilke, an anomaly for me – are also wedded to ‘simple’ language and seemingly simple statements: Mayakovsky, the late Apollinaire, the late Neruda, Zbigniew Herbert.

Philip Larkin is not a poet of the vernacular, though he uses it often enough. But I have found, in recent years, that reading him is like a salutary dose of directness in a world where too often circumlocution, avoidance and outright lies seem to hold sway. I did not always love Larkin: I read his Collected Poems and was relatively unmoved. ‘Ah,’ I thought, ‘those Brits like their poets narrow and pedantic and unadorned.’ I should have known better – that ‘unadorned’ is something that usually attracts me.

A while back I set up the curriculum for a first-year seminar that was to examine what poetry has to teach us about life, about living, about ethics. At the last minute, I thought maybe I should consider the poem this letter begins with, “This Be the Verse.” My son David always tells me it is his favorite poem and has asked me on occasion whether I teach it. Well, now’s my chance, I considered. One poem would not be enough, of course, so I pulled out my Collected Poems of Philip Larkin and began to read. All I can say of that experience is, Wow!

What a poet Larkin is. He tells us things we need to know, and doesn’t pull any punches. So this letter will be a longer one than usual, since I intend to discuss three poems by Larkin.

The first you have already read, since it appears at the start of this letter. I have read it, mostly to the delight of students, in many classes. (It tells a great truth, as you can see, and my students can recognize that truth when they see it.) It also is, to my mind, the most transgressive poem I know. The first line does it. First, there is that verb, the single most transgressive verb in English. Not to be mentioned in polite company; often to be apologized for after having been spoken; littered all over the non-poetic speaking universe, but almost never uttered within the universe of ‘poetry.’ “Fuck.” And to compound that, the line violates, most directly and profoundly, one of the Ten Commandments (in some versions the fourth, in some the fifth): “Honor thy father and thy mother.” Not for Larkin:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

He is pretty funny, too, giving them an out yet pinning them mercilessly to the wall, and adding that they compound the errors of their ways, of their psyches, as they “add some extra, just for you.” I have yet to find a student who doesn’t understand what Larkin is saying.

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Some students add a mental reservation, or even voice it: ‘Well, that is perhaps true of my parents, but they did the best they could, and they loved me a lot.’ Still, for all of our (legitimate) arguments that the sins of the fathers are not, or should not be, visited upon the sons, we all know that our parents mess us up. We knew that before Freud, who only confirmed what every human knows: part of what is ‘wrong’ with us comes from our upbringing. They mess us up, I just wrotee, but Larkin – who I have been pointing out is direct and blunt – will not allow me to slip away into imprecision: “They fuck us up.”

The second stanza gives them an ‘excuse,’ for “they were fucked up in their turn.” This central section of the poem is a kind of comic relief, giving us references to a Victorian era, “old-style,” be-hatted and be-coated, that was stern in a soppy sort of way. But always, for the comedy does not win out, there is struggle for mastery, as even our forebears were “at one another’s throats.”

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

So where are we as we enter the final stanza? The family, so often lauded, has been revealed as the site of our personal shortcomings, and, larger, disasters; this is not unique to an individual or even a generation, but is revealed as part of what human beings do to one another when they live within the confines of a family, even if it is loving and has the best intentions of providing a nurturing environment for children to grow up in.

It is universal. The final stanza begins, with a blunt statement: “Man hands on misery to man.” And history is no help: we are not in the nineteenth century here, with its belief in progress, nor even in the best of twentieth century beliefs, which had to do with the perfectibility of society. No, misery is handed down, and it gets worse just as the ocean waters deepen the farther one moves from shore: “Man hands on misery to man,/ It deepens like a coastal shelf.”

But the poem is not done with being transgressive. I used to read the next line as vaguely recommending suicide, until my first year students revealed to me that it probably has to do with escaping family life: “Get out as early as you can.” Transgressive? Beyond that. No holiday parties, no calls on birthdays, no going to family dinners or worshipping together, no visits or even phone calls to stay in touch.

And then, the last and final line: humorous on its surface, deeply distrustful of human life and human community underneath. “And don’t have any kids yourself.”

My own counsel, my deepest counsel, is exactly opposite to what Larkin proposes in that final line. Human continuity, giving love unstintingly, caring: all of these seem to me what we should strive for in our lives. But Larkin, building on what each of us has recognized, “They fuck you up, your mum and dad,” takes us where we would prefer not to go. The only way out of the cycle of suffering and inadequacy, or deep character flaws and wounded self-esteem, is to end the cycle. Get out, and don’t have any kids yourself.

I think he is wrong. His logic is implacable, and for that I honor both him and the poem. But we have faith: in life, in family, in love, and so we go on having families and reproducing them. I sometimes wonder if the humor that suffuses the poem – its street language, its joke about ‘extra,’ its ludicrous portrayal of our forebears as fools, and finally its barely-to-be believed, transgressive concluding line – doesn’t ironically undercut the serious claim the poem makes. I love the poem, I admire its devastating logic, but finally I don’t believe Larkin. He tells the truth, and yet, and yet, maybe there is something other, something that the humor hints at, a capacity for necessary self-delusion that makes life worth living.

To see Larkin as conflicted and not as straightforward as he appears we shall turn to another poem. It is on the same subject as Richard Wilbur’s “The Death of a Toad.” Both poets consider a small animal accidentally killed in the act of mowing a lawn. I love Wilbur, who in the later twentieth century when almost all poets had abjured rhyme and meter and poetic language, refused to leave any of these poetic artifices behind. He is a great poet.

But Larkin? Traditional though he sometimes is (“This be the Verse” rhymes in the most conventional of ways, and is written in iambic tetrameter), this poem has neither rhyme nor a regular meter. In it, lines are often enjambed: spilling over into the next line. Opposed to this ongoingness, there is often a caesura (a pause in the middle of the line) that stops the forward movement of the poem.

Mower

The mower stalled, twice; kneeling, I found

A hedgehog jammed up against the blades,

Killed. It had been in the long grass.I had seen it before, and even fed it, once.

Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world

Unmendably. Burial was no help:Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same; we should be carefulOf each other, we should be kind

While there is still time.

This was the poem that settled for me the notion that Philip Larkin is a great poet. I do not mean to harp on death, although this and the following poem take it as a central subject. But, to my mind, after all the explanations and mystifications and complexities that artists and philosophers bring to the subject of death, nothing is more succinct or more true that the line at the center of the poem, after the hedgehog has died. “Next morning I got up and it did not.” I say that a lot, these days, to myself: it is as if I had encountered, in simple language, a great truth. “Next morning I got up and it did not.”

But I am getting ahead of myself. The poem begins with an action, though actually it is an inaction: “The mower stalled, twice.” The poet kneels down to see why the mower has stalled, and finds a hedgehog – a quilled small animal, about the size of a chipmunk, equally ‘cute’ and appealing, which has been caught in the blades – Larkin is more descriptive, indicating that the mower stalled because the hedgehog was “jammed up against the blades.” Dead, or since the poet is the begetter of this situation and it has a prime cause, “Killed.” As in the earlier poem, where parents pass on their faults without meaning to – “they may not mean to, but they do” – the speaker indicates he did not intend this killing. The hedgehog “had been in the long grass,” and we may properly infer that the mower pushing his machine did not see it before it got caught in the moving blades. In fact, he points out, he has earlier seen and even nourished this hedgehog.

But, even though unintentionally, “Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world.” I said the poem had no rhymes. But it has a rhyme here, “un-,” bridging the enjambment, leading to the shocking caesura.

Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world

Unmendably. Burial was no help:

“Unmendably.” An extraordinary word, here. Nothing can bring back the dead. Death cannot be mended. Even though the hedgehog was small, even though it lived in a nonobtrusive world below the tops of the ‘long grass,’ death has its dominion and it is absolute. “Burial was no help:” The colon urges us onward, for the statement is not final even though it appears to be. We leap to the next stanza and arrive at the line I have already pointed out. It is so clear, so incontrovertible, that it bears repeating. Nowhere have I encountered this blunt a statement about what death is:

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The poem is not over. Along with the blunt directness for which I honor Larkin, a directness which is part of the reason I read his poems and then read them again, there is more. Long ago I sent out a poem by Robert Frost called “The Oven Bird,” which ends with a remarkable question about the bird’s song “The question that he frames in all but words/ Is what to make of a diminished thing.” What, Larkin asks us, are we to do in a world where death is final and occurs almost as if by accident,? “Burial,” he tells us, “is no help.” We must go on living even as death punctuates the world about us, renders final something that we had expected would be ongoing. And then he offers his counsel:

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same; we should be carefulOf each other, we should be kind

While there is still time.

The directness of “They fuck you up, your mum and dad” and “Next morning I got up and it did not” is to some small degree assuaged by the poet’s awareness that we must, therefore, “be careful/ Of each other.” I find great solace in his words counseling us to “be kind” because they come from a poet who does not go in for sugarcoating, who does not leap over the difficulties we confront, be they the poisonous cycles of family life or the ‘reality’ and finality of death.

There is a virtue to the directness that Larkin embraces. He can tell us hard truths, but he can also, with the authority of a truth-teller, tell us to “be careful/ Of each other, we should be kind.”

We now turn to the longest and most complex of the three poems by Larkin I want to discuss. An “aubade” is a poem about, or appropriate to, the dawn. This poem is both rhymed and metrical, and both of these are far more complex than in “This Be the Verse.” The poem is in iambic pentameter (with the exception that the penultimate line of each stanza is of six or seven syllables – save that this line is, in the final stanza, only five syllables.) The rhyme scheme of each stanza is the same: ababccdeed. As in the previous poem, there is a lot of enjambment and caesura: despite the rhymes, many lines are not end-stopped.

There is much posturing about death, not only in life but in literature and religion and philosophy. It is heroic; it is to be feared; it defines both life and what is real in life. Theater confronts dying and death (opera too!), novels treat of it endlessly. Poems use it as a central thematic and as a recurrent subject. Between the quiet fortitude of Socrates feeling his limbs grow progressively colder at the end of the Phaedo and our own day, much has been written about death. Maybe King Lear comprehended it. Mostly, we live with posturing. Not Larkin. This is, in its refusal to see death as redemptive or constructively defining, a great poem. A poem which tells us the truth, a poem which, despite its many verbal adornments, looks at mortality unadorned.

Aubade

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

—The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused—nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

The poem begins, as we have come to expect from Larkin, with a straightforward, unornamented statement of life as he lives it, working all day and coming home to get half drunk – an indication that life is not all that great (the work will return, in the shortest and next-to-last line of the poem) and an intimation that the night may hold its own terrors.

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

The second line provides the predominant setting of the poem: this poem is in the great tradition of Edward Young’s “Night Thoughts” (1742, and continuing to 1745), in which the middle of the night is the occasion for thinking about death. (Young’s meditation also was a precursor to Thomas Gray, Wordsworth and Goethe). The speaker of the poem awakes in the middle of the night, “awaking at four,” and looks to the windows, where he knows that dawn will eventually appear. But before the light comes, he faces the night, and thoughts of death. Dawn may come, but so will death, and each day he is closer to his final end.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Kind of stupid, thinking of death, for it gets him nowhere, and so he calls it: fruitless, an “arid interrogation.” “Yet,” he is fascinated by, gripped by, thoughts of “dying, and being dead.”

Were the poem to end here, we might call it an existential encounter, the “being-towards-Death” that Heidegger liked to write about. But I think that in his night thoughts Larkin is more real, more connected to what we actually think and feel, than the philosophical musings of Heidegger. Poems connect us to ourselves, to how we live and how we feel, not just to how we think. (And Heidegger was a thinker, maybe too cut off from human reality even though he claimed to be plumbing it. Watch out, a surly opinion is coming: thinking too much about being-towards-death hardened him, and the Nazis, from the dark reality that human life is worth more than human death.)

Amazing, really, that in this night poem, this poem about awakening in the darkness of the middle of the night, that Larkin uses the word ‘glare,’ which builds upon the “flashes” of seeing death in the first stanza. Although the room is dark, the mind and its affects are not; death and extinction are felt as a ‘glare’ in the darkness.

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

—The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused—nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

How astonishingly economical these lines are! We fear death not because of remorse – that great Baudelairean emotion – over what we could have done and didn’t, nor do we fear death because it has taken us so long to get over the wrong beginnings (I can’t help but think of the start of “This Be the Verse”) we have perhaps finally surmounted, or may forever be trying to surmount. No, what is so fearsome about death is extinction, “the sure extinction that we travel to,/ And shall be lost in always.” Here, though, is where Larkin is so brilliant. “Extinction” is a word a philosopher or scientist could use. What precedes and follows that sentence, though, is what we feel: we, speaker and reader alike. “The total emptiness of for ever.” Even that is too abstract, and so Larkin gives us this: “Not to be here, / Not to be anywhere.” Nonexistence is a category, but “not to be here” is something close to what we would call real. And that condition is, for the night-thinker, not far off. We live in time, and time moves on, death is “a whole day nearer now” as he wrote in stanza one. “And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.”

Larkin, in the next two stanzas, strips away our defenses. There is “nothing more terrible” than death, than our “not being here.” It is “what’s really there,” and our protections from that knowledge do not help us. Not religion, not philosophy. Here we go on a vertiginous ride through humankind’s defenses, ending with what is truly terrible:

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

I love that destruction of the consolations of religion, “ that vast moth-eaten brocade/ Created to pretend we never die.” If we unpack the metaphorical language, religion is an ornate covering fabric (thrown over the idea that we will die, and forever) that sounds good (and comes to us, so often, with music!) but that has been eaten away by time and the moths which live in time. This is the poem at its most poetic, full of figurative language:

Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die.

It is succeeded by the protection philosophers erect, though Larkin shows that reason refuses to go as far as it could, and so he dismisses philosophy as “specious stuff,”

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel,

Death is the end of consciousness, and so we cannot fear what we cannot be conscious of. That, at least, is what philosophers say.

Not Larkin, for the line charges on, not stopped by a period, to conclude with the “total emptiness” he had referred to in the previous stanza. Terrifying, that Larkin shows us what is coming and leaves us no defense. This, I think, is as good as poetry gets: treating of important things, telling us something we need to hear but cannot bring ourselves to pay attention to because we live enmeshed in the cotton wool of a dailiness that deadens us to our condition:

No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

Nothing but negation here. We are set up by a “no” and a “never” earlier in the stanza. Let’s count up the negatives in the just cited lines: “no… not… no… no… no… nothing… nothing… none.”

And this is only partial, since the “no sight, no sound/ No touch” in series precedes an implied ‘no taste, no smell’ just as in the next line “nothing to love” precedes the implied “nothing to link with.” And there is no escape from this “sure extinction.” It is forever. “The anesthetic from which none come round.”

The poem, as the night continues, dives deeper and deeper into that terrible darkness that is “no sight, no sound,/ No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,/ Nothing to love or link with.”

And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

It may be almost beyond sight, even in the darkness of night, “a small unfocused chill,” no longer that first flash he felt at the end of stanza one. But the awareness of death stops everything, “slows each impulse down to indecision.” Once more, Larkin demonstrates his remarkable ability to put into the language we use every day the certainty of death: a certainty, that we avoid or about which we so often circumlocute rather than face directly. (Who, save Larkin, can face it directly?) “Most things may never happen: this one will.”

We cannot stand this thought, and so in incandescent heat we rage about it, or – far more likely – we seek to blot it out with drink or small talk or holding on to another. The rage, he tells us, comes only when our usual defenses fail.

What impresses me about Larkin is that he will now allow us our normal avoidances. “Courage is no good,” he states rather flatly, nor is ‘Being brave.” Courage, the stoic stance, is a mask we put on so that others will not fear what we so deeply understand is coming, sooner or later. Bravery? “Being brave/ Lets no one off the grave.” (The rhyme at the end of the shortened line sounds almost childish, almost foolish: bravery, then, is kind of a joke.) It does not matter how we face death: it comes, for “Death is no different whined at than withstood.”

Ponder that last line. None of us wants to whine, to cower in cowardly complaint, yet whining is no different, in this line of his, than withstanding death with courage or bravery. Death is coming, and we cannot avoid our end. Thus the poet thinks in the darkness of the night.

But this is an aubade, and dawn eventually comes.

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

As the light slowly strengthens, the night thoughts fall away and the room takes shape. Yet there it is, what we recognized in the dark hours. The light may suffuse the room, but the wardrobe is there, plain and solid, and so is what we understood in the darkness. Death, sure and total extinction, is what is ahead of us, even if once the day dawns we cannot accept this knowledge.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept.

It is not that the brocade of religion again covers things, or that the consolations of philosophy comfort us: we just cannot accept the certainty of death. “One side”, the poet tells us, “will have to go.” I have difficulty, I confess, with this line. On the one hand, it is we who will have to go; after all, we have already learned that “Death is no different whined at than withstood,” and although we can whine, we cannot withstand that “sure extinction that we travel to/ And shall be lost in always.” On the other hand, as the light widens and the day resumes, what has to go are the thoughts we had all night, the thought of “sure extinction.” Soon, the shortest line in the poem will hammer home the truth of dailiness: “Work has to be done.” That work, in offices and in our homes, awaits us. All the world of society is ready to open up before us, as in the wonderful and terrifying line, “Meanwhile, telephones crouch, getting ready to ring/ In locked up offices.” (Certainly I am not alone in hearing an echo of one of the great poems of the twentieth century, Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” in that strange word and rhyme, ‘crouch’. Here is Yeats’ famous conclusion to “The Second Coming:” “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,/ Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born?” No one but Yeats could have written that word, ‘slouches;’ I am equally convinced that no one but Larkin could have written that ‘crouch.’)

The sun comes up and the great social world arouses and appears. Larkin is not done with us. Three astonishing adjectives describe the world that is appearing.

And all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

Let’s look at those adjectives. The world does not care, for us or about us: ‘uncaring.’ The world is, as we recognize it to be, complex and in its complexity close to incomprehensible: ‘intricate.’ And it is ours only for the short term (death recurs, here) for we do not own it, but rather ‘rent’ it.

There was a moment of hope, I think, when the sun arose and the visions of the nighttime were driven back, although what we learned in the night stands “plain as a wardrobe” when the light suffuses our bedroom and reveals, as well, an actual wardrobe. But the dawn is not glorious, not in this poem. “The sky is white as clay, with no sun.” This is no conventional aubade, celebrating the start of day. White, flat, sunless – and it occurs to me as I write this that the reference to ‘clay’ may have symbolic overtones as well, referring to the elemental materials out of which we are made and to which we shall return.

What are we to make of the last line, about “postmen like doctors go from house to house”? You got me. I have no idea. Write me if you do.

So we leave Philip Larkin behind, a voice who speaks plainly, although in his plainness eloquently, about the lives we live. Stéphane Mallarmé began a poem, famously, ‘The flesh is sad, alas, and I have read all the books.’ (La chair est triste, hélas ! et j’ai lu tous les livres.) Critics and scholars laud him as the voice of the future. A close friend was deeply insulted when I cited the last lines of Larkin’s short lyric, “A Study of Reading Habits” even though what Larkin says is not far from the words of the French poet. I’ll end with the line nevertheless: Larkin remains transgressive, colloquial, telling the truth as he sees it, even as the truth he tells us is possibly ironic (for it is said, after all, in a poem). “Get stewed:/ Books are a load of crap.”

Goodbye, Philip.