Gwendolyn Brooks, “We Real Cool” and “The Chicago Defender Sends a Man to Little Rock”

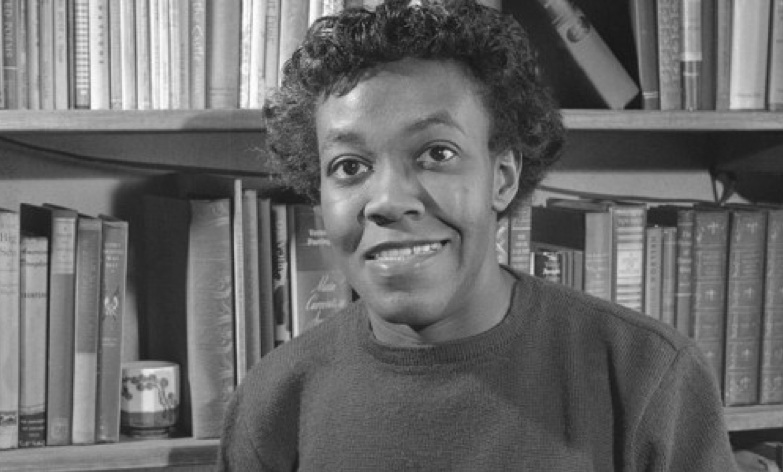

Gwendolyn Brooks

When I returned to re-read this essay, I was struck by how ‘ethical’ its orientation was. I began the essay in Washington, focusing on a line that has always been terribly important to me. But I got hung up, as I acknowledge in the essay, by a stanza I did not understand in the longer poem. Thus, what I had to say about Gwendolyn Brooks lived in my computer’s files and not in the world beyond that.

Two things drew me back to this endeavor of addressing Gwendolyn Brooks. The first was that I taught “We Real Cool” in an introductory poetry course and had, as I was preparing to present it in class, what I might call an epiphany. A poem I had read in one way, a way that never really satisfied me, now appeared in a very different way to me. Which is part of the reason this chapter is called, “Without Preconceptions.” We are so happy to have figured things out that we fall back, time and again, on what we have figured out and thus, in some sense, stop thinking any further.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, the only non-economist who has won the Nobel Prize for Economics, recently wrote a book that hit the best-seller list and stayed there for a long time. Thinking, Fast and Slow. I imagine it was mostly a coffee-table book, because it is tough reading, and each chapter has study questions at its conclusion.

But I found the book an eye-opener. I loved it precisely because it proceeded in directions very different from those in which my thinking went. I loved its challenge to my own habitual ways of thinking. It was, and remains, the one of the most exciting books I have read in the past decades.

Like another immediate economic best-seller (also a tough read), Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century[1], its thesis is simple. Kahneman says that we have two ways of thinking, fast and slow. The first, type one thinking, is kind of automatic, proceeding down a route we think we know. That makes it possible for us to avoid a crisis of consciousness: I can’t really ask myself, every time I see a wall, if it is solid or if I might be able to walk right through it. There is another kind of thinking, slower, that makes us consider the question we are confronting and how to resolve it. This ‘type two thinking’ requires work and time. We don’t always want to work and we often want to save time. So we avoid this ‘type two’ thinking whenever possible. In doing so, Kahneman claims, we make mistakes.

That’s it. I guess in some way I was prepared for Kahneman because, as you know if you have read previous letters, I have been much influenced by an essay by Viktor Shklovsky in which he says the fundamental characteristic of poetic language is that it slows us down and forces us to consider both words and things so we don’t encounter them automatically. Poetry helps us live our lives. It is an alternative to our proceeding as human ‘machines’ through our daily existence. Poetry, if I were to use Kahneman’s terminology, insists on type two thinking.

I diverged into Kahneman because he provides a theoretical matrix for what I experienced. For forty years I read “We Real Cool” one way, without stopping to think that there might be another way.

Writing about “We Real Cool” brought me back to the analysis I had started on “The Chicago Defender Sends a Man to Little Rock.” I pushed myself to finish what I had started, even if the troublesome stanza which had held me up remained troublesome.

As I said in starting out on this headnote, I found that when it was completed, this essay had taken a deeply ‘ethical’ direction in assessing the second poem. The previous letter, on Zbigniew Herbert’s “Envoi,” also was an ethical exhortation of sorts. I think I know the reason why.

I had returned to teaching. I have always told my students – I believe this strongly – that a class is not a church, and there is no requirement to ‘believe’ anything that the teacher says, or for that matter what a poet says. Still, in a society where the ethical path seems to be far less important than making money or gaining status or playing computer games well, who will teach us how to live? I think poets try to do that, and although they are very often as flawed in their thinking as others are, the seriousness of their concern demands that we take their efforts seriously.

This essay, then, was an effort to show my students how to live. Is what it claims, what Brooks suggests in her poem, correct? I can only repeat, a class is not a church. There is no requirement that we believe.

But we might bring what Kahneman calls type two thinking to bear and consider, seriously, the questions Brooks raises for us.

As I write this, it is the season of college graduation. A reference in a column in the New York Times prompted me to look up the remarkably fine commencement speech novelist David Foster Wallace gave at Kenyon College in 1995 Ah, the wonders of the internet.

Here is just a small part of what Wallace said about how college teaches young people how to think:

The point here is that I think this is one part of what teaching me how to think is really supposed to mean. To be just a little less arrogant. To have just a little critical awareness about myself and my certainties. Because a huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded.

I want to look at two poems, one of which I was automatically certain of – and so deluded by my certainty that I could not understand the poem. The other is in a way its polar opposite: something in the poem resonated in me so strongly that it confirmed one of my deepest – and I think my best – beliefs. Though that meant with this poem, too, I too often have missed understanding the poem in all its complexity.

Both poems are by Gwendolyn Brooks, who in 1950 became the first African-American to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry for her second book, Annie Allen. One of the poems is short, the other moderately long.

The short one first. It is, I think, her most well-known poem. I have read it for over forty years but only this spring was I able to see it clearly. And that was because for reasons I don’t fully comprehend, I was able to shed my in-built and deep preconceptions.

Here’s the poem. As I just said, it is short – remarkably short.

We Real Cool

THE POOL PLAYERS.

SEVEN AT THE GOLDEN SHOVEL.We real cool. We

Left school. WeLurk late. We

Strike straight. WeSing sin. We

Thin gin. WeJazz June. We

Die soon.

First, the arithmetic, which reveals how remarkably well-made these lines are. Eight lines, in four stanzas of two lines each. Twenty-four words. (Also, twenty-four syllables, since all the words are monosyllabic.) The first line contains four words, the final line two. Here is what is remarkable – perhaps unparalleled? – in its construction. Every line but the last line rhymes with every other. (There are eight ‘we’s in the poem.) The second word of the first line in each stanza (well, not the first line, where it is the third word) rhymes with the second word of the second line in the stanza. Additionally, in lines three through seven, the first two words alliterate[2]. [Additionally, the first words in lines of the middle stanzas are slant rhymes: Lurk/Strike, Sing/Thin.] The only word in the poem that neither rhymes nor alliterates is the ‘die’ of the last line, a circumstance which would seem to emphasize the otherness and finality of death.

Or if that is too much arithmetic to absorb at one go, of the poem’s 24 words, only a single word does not rhyme or alliterate with a word near it. “Die.” An amazing tour de force.

I could always see that. What I couldn’t see was the poem. I have always wanted, insisted, that it be some form of social commentary.

Wrong. I believe I mentioned in a previous mailing the great first line of a late poem by Wallace Stevens, “The poem must resist the intelligence almost successfully.” That poem, “Man Carrying Thing,” is a strange poem itself, resisting the intelligence in a way the first line proposes. But the last line, coming after a convoluted and indecipherable metaphor about a nightlong winter snowfall, is clear in two senses: it is about a bright un-snowy dawn, and the line is absolutely clear in what it describes, “the bright obvious stands motionless in cold.”

Once I shed my preconceptions about “We Real Cool,” the bright obvious stood motionless in the cold. The poem is not commentary but re-creation. I had wanted the poem to say something about marginal black youth, about the seven guys who hang out around the pool hall, the Golden Shovel. I wanted it to be a commentary on ‘wasted lives’ or a condensed meditation on an existential intensity to lives lived outside the frame of history and public discourse. After all, the latter is the subject of many of Brooks’ poems.

Nope. It’s neither of those.

It is something harder to accomplish and to my mind more important. It is a revelation of lives lived other than my own, or quite possibly other than those of you who are reading this.

I had so much wanted leaving school and sinning and drinking and playing pool to connect up, in some fashion or another, with ‘dying soon” that I could not see what was happening in the poem, something that is at once simpler and tougher than any social commentary or societal analysis.

In my favorite poem by Robert Lowell, “Epilogue,” (maybe I will write about this poem later? Stay tuned . . . ) Lowell writes, “Why not say what happened?” That is what Brooks is doing. Saying what happened, and what happens, beyond our visioning. In the real world, not the world we imagine in our flights of fancy.

There are millions of young black men in America, even today, who think themselves cool. They quit their education before graduating from high school, they are more likely denizens of the night than the day, they engage in violence. (Or does ‘strike straight’ denote a fundamental honesty? I’d say: both.) They engage in wrongdoing. They are deep into what we call ‘substances’ (alcohol, but also drugs). They “Jazz June” in that they are hooked into music (today, more likely rap than jazz), into an edgy joy in life regardless of consequences. And often they die: of violence, of drug overdoses, of the life-sapping consequences of high stress, poverty, and lack of adequate access to health care.

Kind of stark and sociological, the way I have just summarized the poem. Notice two things. First, I used a lot more words than Brooks: while I am prolix and dull, she is economical and vital. More important yet, she gives a sense of the ‘life world’ the young men live in, and well, I just I gave a turgid, tiresome and kind of unapproachable description of a world we have encountered (in words) so often before that any verbal recapitulation has become trite.

Brooks adds to our experience and knowledge of the world. My summary bores us by telling us once again what we have so often heard that we discount it entirely.

So it is no small accomplishment that Brooks has achieved. She shows us the world, instead of telling us about it. For let me mention one aspect of the poem I have skipped over. It is not Brooks who is speaking. The first person plural that recurs in each of those first seven lines is the pool players. We overhear their sense of their lives. We encounter them.

These seven young men are not doing social commentary, nor are they simply describing the world. They are allowing us to enter into the world as they experience it. So Brooks does more than the Robert Lowell counsels: more than ‘saying what happened,’ she shows us what is happening. That’s it. Less is more. We experience, through the words of these young men, a world we cannot see except from outside, objectified. Though there are of course some readers who may, through direct experience, see it: for them too the poem allows the directness of experience, of succinct but penetrating experience.

Let me return to David Foster Wallace. If in reading this poem we want to encounter its power and its significance, we have to give up our desire to have the poem ‘mean’ something. We have to get sucked in. That does not mean we have to surrender all our critical intelligence. We can still think about the importance of education or the dangers of substance abuse or the tragedy that so often afflicts young black men. But that thinking is after the poem, not in it. The poem comes to us like primary sense data, before interpretation.

It is all the rage to say, nowadays, that the world is ‘always already’ interpreted. Maybe it is. But if we think that way, we are liable – as I did for four decades – to miss the deep significance of “We Real Cool.” Which is that the poem does not signify, does not interpret: it presents us with a reality that is good for us to encounter. Good, in the sense that it enlarges us; good, also, ethically, in that we are better human beings if we understand, existentially, the lives of others and not just our own life.

Unlike the other poems I have discussed in these mailings, I don’t have to work through this poem line by line. This poem asks, requires, that you hear those seven young men directly – not through any intervention of mine. They present their lives to us, in their words. We need to listen to them so that we can see them and their lives.

Now I proceed on to another poem by Brooks, one I value deeply. Let me approach it by indirection, since as Emily Dickinson once wrote, “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant/Success in Circuit lies.”

Perhaps eight years ago I was reading the Sunday New York Times when at the back of the Book Review I came across a paean to a book about philosophy, a book which took as its subject the early history of Western philosophy. The piece was written by the editor of the Book Review. He highly recommended the book, What is Ancient Philosophy? by Pierre Hadot[3]. I was intrigued by the review, and intrigued by the mention that Hadot had been a teacher of Michel Foucault, a philosopher/historian/social theorist who had been a teacher of mine.

Uncharacteristically – I usually read the reviews and eschew the books – I went out and bought What is Ancient Philosophy? I read it with excitement and joy, and two years later I read it again. I recommended it to friends and continue to do so. It is the best book on philosophy I have ever read.

Its central thesis is that philosophy, for the ancient Greeks, was not an academic pursuit but the natural outgrowth of the question, ‘How shall we live?” And that question was never asked in some sort of meditative state, divorced from the world: philosophy as we know it developed in schools (first Socrates’ peripatetic interlocutions with his students, then Plato’s Academy, then Aristotle’s Lyceum) which were dedicated to teaching young men how to live. Hadot is critical of the development of Western philosophy, which has turned away from the practical ethical focus of ancient philosophy and moved into the production of philosophical discourse: words, not lives, seem to him to have been the stuff of philosophy for most of the last millennium.

I begin with philosophy, with Hadot, for a reason. When I was young, I sought wisdom in poems. (I still do, if truth be told.) But reading poems for many years has taught me that they are not really the province of wisdom. Poems, lyric poems in particular, illuminate and enrich our emotional lives. Sometimes, as in exploring loneliness or love or uncertainty about death, they show us we are not alone in our feelings, and by documenting that emotion with clarity they give us a better sense of what it is that we feel. Sometimes, equally important times, poems show us what other people feel.

Solipsism, the capacity of seeing only ourselves, is a constitutional hazard of the human condition. But it is important, and in actuality it is essential, that we understand not only that there are other people like ourselves but that other people can also be different from us. (That visible ‘otherness,’ we have just seen, is the point of “We Real Cool.”) Poetry can lead us out of the prison of the self. (So can novels, drama, music, painting, all art…) In this regard, I always think of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the most important (but not the best! and certainly not the wisest!) poem of the twentieth century. Near the very end of the poem, as an illustration of the Sanskrit term Dyadhvam (which he translates in a footnote as “sympathize”), Eliot writes:

I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison . . .

Poems, then, are sometimes a key which unlocks the wider world, and lets us see and feel the lives of people who are other than ourselves.

Rarely are poems a source of wisdom. Poets are too concerned with describing what the world feels like, and shaping for us what their own feelings feel like, to be the best guides for how to live. They push forward – they make poems out of their arguments with themselves, and their arguments with the world, and their failures to win many of those arguments – but they don’t usually reach some Mosaic promised land where they reside in the land of wisdom.

The Chicago Defender Sends a Man to Little Rock

Fall, 1957

In Little Rock the people bear

Babes, and comb and part their hair

And watch the want ads, put repair

To roof and latch. While wheat toast burns

A woman waters multiferns.Time upholds, or overturns,

The many, tight, and small concerns.In Little Rock the people sing

Sunday hymns like anything,

Through Sunday pomp and polishing.And after testament and tunes,

Some soften Sunday afternoons

With lemon tea and Lorna Doones.I forecast

And I believe

Come Christmas Little Rock will cleave

To Christmas tree and trifle, weave,

From laugh and tinsel, texture fast.In Little Rock is baseball; Barcarolle.

That hotness in July . . . the uniformed figures raw and implacable

And not intellectual,

Batting the hotness or clawing the suffering dust.

The Open Air Concert, on the special twilight green . . . .

When Beethoven is brutal or whispers to lady-like air.

Blanket-sitters are solemn, as Johann troubles to lean

To tell them what to mean. . . .There is love, too, in Little Rock. Soft women softly

Opening themselves in kindness,

Or, pitying one's blindness,

Awaiting one's pleasure

In azure

Glory with anguished rose at the root. . . .

To wash away old semi-discomfitures.

They re-teach purple and unsullen blue.

The wispy soils go. And uncertain

Half-havings have they clarified to sures.In Little Rock they know

Not answering the telephone is a way of rejecting life,

That it is our business to be bothered, is our business

To cherish bores or boredom, be polite

To lies and love and many-faceted fuzziness.I scratch my head, massage the hate-I-had.

I blink across my prim and pencilled pad.

The saga I was sent for is not down.

Because there is a puzzle in this town.

The biggest News I do not dare

Telegraph to the Editor's chair:

“They are like people everywhere.”The angry Editor would reply

In hundred harryings of Why.And true, they are hurling spittle, rock,

Garbage and fruit in Little Rock.

And I saw coiling storm a-writheOn bright madonnas. And a scythe

Of men harassing brownish girls.

(The bows and barrettes in the curls

And braids declined away from joy.)I saw a bleeding brownish boy. . . .

The lariat lynch-wish I deplored.

The loveliest lynchee was our Lord.

I began with philosophy and Hadot because the poem by Gwendolyn Brooks we are about to examine has a line which, to me, has always been one of the guiding poles of ‘wisdom’ in and for my life. I know, I know, that I always take the line out of context – we will look at that context in generous detail. But when the speaker of the poem says, “In Little Rock they know…that it is our business to be bothered,” he tells me something of great significance. What he is saying about the citizens of Little Rock is that they know how deeply important it is that we not turn away when we are bothered, that our life’s business is in responding to these ‘bothers.’ I remind myself of that, I say that line to myself, at least once a week, and I have done that for the past forty years.

The speaker is, in his own American idiom and in his 20th century persona, channeling something like the great lines from Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey,” when the speaker proposes “that best portion of a good man’s life” is “his little, nameless, unremembered, acts/of kindness and love.” It is our business to be bothered, to answer the telephone, to respond when people ask things of us or when they bring their presence or their needs in proximity to our own presence in the world of daily interactions.

I first encountered the poem when I was teaching from an early ‘textbook’ of black American writing, in – this seems so long ago – the very early 1970’s. I have read a lot of Gwendolyn Brooks since then, and know that she wrote better poems, but that line, “it is our business to be bothered” has stuck with me. And the poem itself, which says something that is diametrically opposed to what is being expressed in the stanza in which the line occurs, is very worth our close attention, even though Brooks wrote stronger poems, better poems. For the poem shows us something that although it was very true of the American South of the 1950’s, also shows us much that may well be true of much our entire nation, and our entire world, in the year 2014.

The Chicago Defender was an African-American newspaper published in, of course, Chicago. As a native of Chicago, as a black woman living in Chicago, of course she read it. In fact, Brooks published her first poems in the Defender. In this poem she imagines a reporter sent to Little Rock, Arkansas to cover one of the most important stories in America in the second half of the twentieth century. Nine students, several years after the momentous decision by the Supreme Court in Brown vs. Topeka that segregated schools are “inherently unequal” and therefore violate the Constitution, enrolled in the all-white Central High School in Little Rock. The governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, called out the National Guard to prevent them from entering the school doors.

President Eisenhower warned Governor Faubus to obey the ruling of the Supreme Court. When Faubus refused to back down, Eisenhower sent Army troops to Little Rock and federalized the Arkansas National Guard to make sure the students were able to enroll. When the newly enrolled young people did enter the school, as the poem makes clear at its conclusion, white men and women harassed, hurled epithets at, and even spat upon the nine black students.

The poem begins with the reporter ‘reporting’ on the ordinariness of life in Little Rock apart from the school integration. For most of the poem, he does not address the attempt to integrate the school, the story he was sent South to cover: the students entering Central High School make their appearance only in the final four stanzas of the poem. People bear children, they comb their hair, they read want ads in the paper, the fix up their homes when necessary. They burn toast and water their plants. (“Multiferns” is an invented term, connoting I think the multiplicity of things that need to be done during the daily round of usual activities, the “many, tight, and small concerns.”)

Of course, irony ultimately shapes the poem. People in the first line bear children, but by the end of the poem it becomes clear that they can on occasion – when it is not their child, when the child is of a different color – totally fail to recognize the humanity of the children they think they love and care for. Their concerns, the focus of their lives, are “tight” and “small.” Throughout the poem, small concerns edge out larger concerns: small humanities crowd out the capacity of the people of Little Rock to see the larger human questions that confront them.

So the people of Little Rock – and by people the speaker of the poem means white people – belt out hymns in church, they dress up, they clean themselves and their cars and houses to worship the Sabbath and the Lord. (I keep skipping ahead to the end of the poem, because there the irony is most clearly revealed: these people are religious only in the small and tight sense of going to church: they are not, in the speaker’s view and in Brooks’ view, religious in the sense that the have any understanding of Jesus Christ.)

After church, after “testament and tunes,” some spend a mellow afternoon with sweet drinks and buttery cookies – Lorna Doones. The reporter continues by predicting that at Christmas, there will be other artifacts of celebrating the birth of the Christ child: Christmas trees, sweet desserts (“trifle”). Out of their activities families will “weave” a lasting texture of holiday togetherness.

But the reporter also looks back (the poem, as the dating following the title tells us, is set in the September of 1957 when the school integration drama is being played out) to the summer that has just concluded, a summer of baseball and concerts in the park. There are undertones in this stanza of something other than “tea and Lorna Doones.” The baseball players in their uniforms, perhaps prefiguring the uniformed National Guard that Governor Faubus called out, are “raw and implacable/ And not intellectual/ Batting the hotness or clawing the suffering dust.” The evening concert in the open air features Beethoven and Bach, the former sometimes “brutal” and the latter celebrating Christ and beauty to an audience sitting “solemn” in their pursuit of cultural betterment – not quite able to understand what Johann Sebastian Bach has to tell them.

[This may be the moment to look at the remarkable, constantly changing rhyme scheme. The recurrence of rhymes – often three in a row, once even four – binds the poem together and lulls the reader into a kind of comfort that is blasted away by the final lines – which themselves rhyme. Of line endings, only air, lean, business, softly and polite do not rhyme, but internally even those lines are rife with alliteration: Beethoven, air, brutal blanket; twilight blanket solemn lean tell; love Little softly; business bothered business bores boredom polite. Here then, alphabetically by rhyme, is the elaborate rhyme scheme of this poem:

aaabb/bb/ccc/ddd/efeef/gg1g1hijh/kllmmnl1l1/opqrq/rrssttt/uu/vvwwxxy/y/z/z ]

Let me confess that I always have trouble with the next stanza. I think Brooks is saying there is love, including sexual love, in Little Rock, but I am not fully sure what Brooks is referring to. One critic thinks it is a brothel, but I find that difficult to believe given the empathy the speaker has for so much of what he finds in Little Rock. (I was so discomfited by this critic’s over-reading of the stanza that when I first started to write about this poem I stopped. That critic is, to my mind, wrong.) Oh, there is criticism in the irony, in the connotations, as the poem proceeds. But as the first-person speaker of the poem will state later, “They are like people everywhere,” which leads me to believe that the lines are serious about the presence of love. (I am not ignoring the ironic presence of love in this poem, of course, given that the white Southerners’ response to the enrollment of the nine black children at Central High, as the poem will describe in its conclusion, was hatred and awful anger.)

So where are we? In Little Rock, the black reporter from the North discovers, people have babies, they burn their toast, they have many daily concerns, they go to church and eat cookies and they celebrate the birthday of ‘our Lord.’ They go to baseball games and listen to music in the parks, they love and make love.

In Little Rock they know

Not answering the telephone is a way of rejecting life,

That it is our business to be bothered, is our business

To cherish bores or boredom, be polite

To lies and love and many-faceted fuzziness.

I’ve already said that a truth expressed in these lines, “that it is out business to be bothered” has been an ethical guide in and to my life. Even now, in our age of caller ID, except for anonymous fund-raising calls, my wife and I always answer the phone. I’m not sure I go as far as suffering bores, and I certainly do not cherish them. But the point the reporter makes, that the ethical life often depends on our understanding that “it is our business to be bothered,” that point is remarkably apt. And wise, it seems to me.

Which is why, more than anything, the reporter confronts what he has assumed – “the saga I was sent for” – and finds it not just puzzling but wrong.

The biggest News I do not dare

Telegraph to the Editor's chair:

“They are like people everywhere.”

His editor would not understand. And would ask an editor’s questions, a “hundred harryings of Why.”

And thus the poem swiftly arrives at its devastating conclusion. The people may be like people everywhere in their “many, tight, and small concerns.” But when history stands before them, when the world’s gaze turns to see how they address another seemingly ‘small concern,’ nine children going to school, they act unethically in the most profound way.

And I saw coiling storm a-writhe

On bright madonnas. And a scythe

Of men harassing brownish girls.

(The bows and barrettes in the curls

And braids declined away from joy.)I saw a bleeding brownish boy. . . .

The lariat lynch-wish I deplored.

The loveliest lynchee was our Lord.

The children, in the final lines, are madonnas, queens of suffering. The bleeding boy is Jesus Christ. The ‘normal’ people of Little Rock, who “are like people everywhere,” are the Roman mob demanding the crucifixion of Christ. So the reporter, who for background found nothing to report other than that the white citizens of Little Rock “are like people everywhere,” deplores the re-enactment of the crucifixion on the bodies of young “brownish” girls and boys walking into Little Rock High School.

With the denial of humanity to these brownish boys and girls, the core of Christianity, and Christ himself, is denied.

The poem presents us with dual truths. One, that “it is our business to be bothered” because we are all human beings, to be bothered by even the bores and the liars: this it seems to me, even though so seemingly mundane and ordinary, is a deep ethical truth. In philosophical terms, the ‘Other’ always has a claim on us. But too often, the poem dramatically signals by its conclusions, if we are wrapped up in “the many, tight, and small concerns,” we do not see that in the midst of those small concerns there are moments when we need to respond with a new openness of vision. The humanity of the ‘Other’ too often may not appear to us because we are blinded by differences. In the case of this poem, by racial differences.

Over the years, as I recall the poem – and I do that, as I said, often – I recall only part of it, the ‘wisdom’ of “it is our business to be bothered.” That line, and the openness of vision of the reporter who sees the white citizens of Little Rock as human beings and not solely as ogres – is part of the ethical core of the poem.

But it is only when I go back and reread the poem, reread all of it, entire, that I see that what I am “automatically certain of” (to circle back to David Forster Wallace) is modulated by another aspect of the poem, which is that accepting ‘being bothered’ is not enough. The poem, in a very powerful way, addresses what has come to be called ‘the banality of evil.’ Ordinary people, going on with their lives in ordinary ways, not questioning their usual and ordinary motivations, the stereotypes in which they so comfortably live, can be complicit in great, even unspeakable crimes.

The white citizens of Little Rock go to church but cannot see the moral dilemma which confronts them. They love their children, but spit on children of a different hue. They are unable, entirely unable, to do for themselves what David Wallace said so clearly: to have just a little critical awareness about myself and my certainties. Because a huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded.

‘How shall we live?’ This is the question the ancient Greek philosophers posed to themselves and their students. Philosophy, as Hadot so powerfully pointed out, is at its base about ethics, about how we live our lives.

The ethical path lies before us every day. “It is our business to be bothered,” and in the way we connect (or fail to connect) up with other lies the moral way. But the ethical path also demands we embrace the critical awareness that will allow us to see what our personal experience has blinded us to. To be ethical, to examine ‘How shall we live?’, we must think critically about the easy route we so often take, that of accepting the world as we have always seen it. For in doing what we always do and have done, we may make ‘totally wrong and deluded’ choices.

In this poem, the reporter who speaks to us is capable of following both paths. The white citizens of Little Rock? Only the first. They fail, totally, dismally, to follow the route of critical self-awareness. In that, they fail the test that history set before them. They have not had the courage to ask themselves, ‘How shall we live?’

And the reporter, who sees both that the people of Little Rock “are like people everywhere” and that at the same time these people are capable of wanting to lynch innocent young children? The narrator of the poem turns out to be, as much as the children attempting to integrate Central High School in the midst of the anger and hatred directed at them, a heroic figure. Observant, self-critical, inclusive, open-eyed, self-correcting, he is for Brooks’ readers a paradigm for the inquiry, ‘How to live.’

Footnotes

[1] I may have intrigued you by that assertion about Piketty. His thesis is remarkably simple. If the economic pie grows at a slower rate than the big slices given to the wealthy are growing, the portions on the plates of the rich will grow larger while the portions of everyone else will grow smaller. Hmmm. The logic seems inescapable, and the statistics Piketty has so painstakingly gathered indicate that, in actual fact, in our contemporary world, in society after society, the wealthy get richer and everyone else gets less than they had been getting.

[2] For those interested in historical precedent, the main form of ‘rhyming’ in Old English poetry. Each half of a line, which had one strong stress or two, ‘rhymed’ with the second half of the line through alliteration.

[3] So strong has been the hold this book hadon me that I have written about it in the previous chapter as well. Redundancy should be avoided in fashioning crisp prose, but not in life. Repetition in life, as in poems, is often a signal that something is vitally important,